5. How dangerous are the new technologies?

It’s the 2000s. Matthias Rath is sitting in the Cape High Court. He is a vitamin tablet salesman and he claims that multivitamins treat AIDS. He also claims that antiretrovirals, the only scientifically proven medicines to treat HIV, are toxic. He runs full page adverts making his claims in the New York Times as well as South African newspapers. He tells cruel lies about doctors and AIDS activists. His claims are outlandish and deadly.

But Rath is never accepted by the mainstream. On the contrary, the major newspapers condemn him. The Cape High Court rules against him — muting some of his false claims. He leaves the country and disappears into obscurity, a conman who fails to develop a significant following, despite having the support of senior people in the South African government including the then Minister of Health.

It’s February 2025. Elon Musk is on the Joe Rogan Experience, the world’s most popular podcast. He tells lie after lie after lie: Democrats are trying to end democracy by putting immigrants into swing states, children are over-vaccinated, millions of dead people are getting social security benefits. This is just a taste of it.

Tens of millions of people listen to Joe Rogan’s interviews with Musk. Rogan riles against the mainstream media publications: New York Times, Washington Post, CNN and MSNBC. “They’re all full of propaganda, and so that’s why the internet rose. It’s not because there was some sort of a fucking right-wing conspiracy, heavily funded,” he says.

But Rogan is the new mainstream media. He has a massive global following with just under 20-million subscribers on YouTube. Yet episode after episode he and his guests mislead with ever more outlandish nonsense. There is now a Know Rogan podcast dedicated to debunking Rogan and his guests. The episode debunking Musk is especially worth listening to.

Matthias Rath didn't succeed in the 2000s largely because his access to the main news publications was patchy. He needed a massive advertising budget for the little traction he got. But in the 2020s he may have succeeded. Today the cost of being a successful charlatans is much lower.

The new forms of media, like the Joe Rogan Experience, are used by people who lie shamelessly to achieve their political ends. This is the approach of the populists worldwide. It’s so much harder to counter it in today’s world compared to the 2000s. In democracies, up to the 2000s, most mainstream newspapers, with editors and standards that they had to adhere to, would have likely muted Musk’s lies. But with the new technologies, the lies appear to be almost unstoppable. This is not to say that mainstream publications were immune from systematic lie-telling; they definitely weren't. But individual billionaire populists, as well as run-of-the-mill conmen, had a much harder time being accepted in mainstream discourse before the rise of the new technologies. It is doubtful Musk could have lied as shamelessly, systematically and continuously as he has the past few years and expected to preserve massive public support. Musk does however appear to have gone too far. His "relentless boorishness" has caused his popularity to plummet.

Voter manipulation using new technologies has become a huge concern over the past decade. The Cambridge Analytica scandal, in which user data on Facebook was used to drive political advertising, received particular attention. Nowadays we suspect the once scandalous techniques of Cambridge Analytica have become almost unremarkable, despite efforts to increase data privacy.

Disinformation using social media has become a crisis for the Baltic countries battling to fend off Russian campaigns. These campaigns are especially aimed at manipulating their Russian first-language citizens though it goes beyond this. In October 2023, Lithuanian authorities reported that the country was “flooded” with about 900 bomb threats against schools and other institutions, in a coordinated attack likely from Russia.

Russia was also accused of running a disinformation campaign ahead of Moldova’s 2024 referendum to join the EU. While the campaign may not have entirely succeeded — Moldova voted to join the EU — the vote was extremely close, much closer than predicted.

There is also concern that the 2023 Slovak election was swung by Russian disinformation. According to Lluis de Nadal and Peter Jančárik in the Misinformation Review: “Two days before the election, a fake audio clip surfaced purportedly capturing [Robert] Fico’s main rival, pro-European candidate Michal Šimečka, discussing electoral fraud with a prominent journalist. Although both quickly denied its authenticity, the clip went viral, its impact amplified by the timing just before the election during Slovakia’s electoral ‘silence period’ — a remnant from the era of legacy media, which prohibits media discussion of election-related developments. Šimečka’s loss, despite leading in the polls, fueled speculation about the election being ‘the first swung by deepfakes’.” (The article from which this is from expresses caution about how to interpret this event and it is worth reading.)

The debacle around the recent Romanian election in which an unlikely pro-Russian candidate won the first round, seemingly following a TikTok campaign, is still to be properly understood. This past week a centrist candidate, who faced a disinformation campaign, nevertheless won the run-off election against a populist. But it was close.

In Sudan disinformation has had deadly effects. SMEX, a Lebanese organisation that advocates for "digital rights" writes about the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), one of the two main militias in the civil war: "Blue-ticked and with over 100K followers, the RSF’s Twitter account and online support network play a key role in spreading disinformation. The page runs unhinged on Twitter, although the paramilitary group has committed countless crimes against humanity in Sudan, raising serious questions about the platform’s commitment to safeguarding human rights.

SMEX continues: "Twitter has aided the RSF by allowing it to exist officially online and giving it a virtual platform for setting its agenda. For example, the most recent assault on the Sudanese capital on May 12 [2023] was marked with aggressive tweets by the RSF falsely claiming complete control of Khartoum and other misleading information. However, trusted media agencies and sources close to SMEX reported ongoing fighting in the capital, contradicting the RSF’s claims."

Much of the disinformation is simply straightforward financial scamming. The Globe and Mail reports that in the 2025 Canadian elections there have been websites with fake AI-generated content showing Prime Minister Mark Carney purportedly endorsing fraudulent investment platforms. A quarter of Canadians surveyed said they'd seen this and other election-related fakery.

It doesn’t require the resources of a state to run disinformation campaigns. The cost and difficulty of spreading disinformation has dropped dramatically. From email lists in the late 1990s to the social media tools of the 2010s, spreading information, both truthful and not, has become easier.

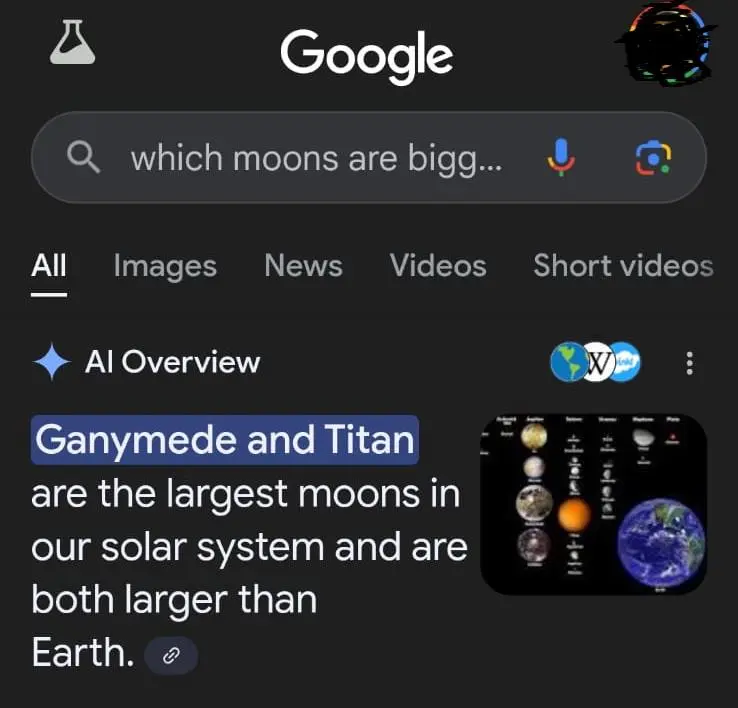

And now there are AI tools like large language models thrown into the mix.

Carl Bergstrom and Jevin West of the Centre for an Informed Public at the University of Washington explain: “Writing one bullshit post on Facebook never took much time, but posting bullshit to a hundred different social media accounts was an afternoon’s work for a propagandist. Writing a disingenuous op-ed could take a day or two. Drafting a fake scientific paper could take a month, and required substantial expertise in the area to be convincing. Today, Large Language Models can do any of these things in a matter of seconds.”

But there is another more positive side to the new technologies too. Quality information and easy-to-follow educational materials are also more accessible than at any time in history. In trying to prevent misinformation one shouldn’t over-correct.

De Nadal and Jančárik in the same article quoted above, write: “Alarmist reactions to misinformation are not harmless; they may lead to counter-measures that, however well-intentioned, might be exploited to police political debate … Policymakers and technology companies must do more to combat misinformation … but one-sidedly framing the new media environment as a threat to democracy … might result in restrictive policies that erode democratic freedoms”.

They explain: “This is not merely a hypothetical scenario: Recent anti-misinformation laws, including in Western democracies like Germany and Hungary, have weakened protections for independent journalism and compromised access to diverse news … Several governments have criminalized fake news, imposing penalties ranging from fines and suspension of publications to imprisonment.”

They caution against “‘technopanics’ … which often obscure underlying problems and encourage responses that could do more harm than good.”

We think this caution is necessary.

In advocating for a right to information, we are proposing efforts to combat misinformation. We suggest these efforts be implemented slowly and modestly, and their effects monitored. If consensus emerges that they improve political discussion, critical thinking and how well informed public discussion is, then they will have achieved their purpose. If not, then it’s back to the drawing board.