2. How the world has changed

“My son is going to grow up in a world that has been fractured by a set of circumstances that the world has not seen for more than 500 years,” says science educator Hank Green.

Green incisively analyses, in a YouTube video, how communication has changed over centuries.

The printing press, invented in the mid-1400s, gave rise to Martin Luther, who led the protestant reformation movement against the dominant Catholic church in Rome. Green explains how Luther changed the world but with him came upheaval: his books were inflammatory, he was the populist influencer of his time and enormous violence ensued.

Green reminds us that closer to our time, in the 20th century, the invention of radio revolutionised media, allowing a single voice to reach millions of people. He gives the example of Father Charles Coughlin, an American firebrand who supported Hitler and antisemitism — he had millions of followers. (He was eventually censored and drifted into obscurity.)

Green doesn’t mention this but movies and television were also massively disruptive technologies that provided new opportunities for propaganda. Leni Riefenstahl’s 1935 Triumph of the Will encouraged Nazi myths. Her documentary about the 1936 Berlin Olympics stoked German nationalism. But there was also Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator which turned Hitler into an object of ridicule for Americans.

The major communication change of our time is, of course, the internet. Governments usually have to license radio and television stations because there are practical limits to broadcasting space. This is not the case for the internet.

Also the cost of running a radio or television channel is large. Websites and social media channels are, by contrast, cheap to run.

Radio, television and print give a few people the means to reach millions. Social media platforms, in contrast, give millions of people the ability to reach millions of people. This is a new phenomenon and, as Green says, we don’t yet know how to deal with it. “We don’t have the techniques to deal with the powerful spell that these systems are casting on our brains.”

This feeds populism, Green explains, which he describes not as an ideology, but as a marketing strategy whose exponents effectively tell their followers: “I see all your problems, and I’m going to solve them.”

Green says: “If you ask a newspaper reporter to go and tell you some problems with the FDA you’re going to need to wait six months while they put together a clear cogent story about something that could be better in the world. If you ask a traditional bureaucrat to try and fix something at the FDA they’re going to come back in four years with a list of things that need to be done and a much longer list of why you can’t do that. But if you ask RFK Jr to tell you what’s wrong with the FDA he’s going to do it on YouTube, Instagram, Facebook, TikTok and four different podcasts by the end of the day. Will he have prioritised accuracy or actionable implementation? No! He will have prioritised getting views on content and he will have achieved that goal because RFK Jr is working in collaboration with recommendation algorithms and he is very good at that. And a really good way to do it is to tell … people that they are being preyed upon by large powerful institutions.”

RFK Jr’s utterances on vaccines are outright misinformation. Another serious problem is extreme bias. Take for example immigration. It is a highly contentious election issue in North America, Europe, Australia, parts of Asia and South Africa. The role immigrants play in an economy, their effect on jobs, housing, social welfare and cultural change is extremely complex. But discussion on social media, especially but not only in anti-immigrant circles, is characterised by over-simplification or “hot takes”. Debates on sex, gender, race and diversity suffer the same ills. Extreme bias coupled with over-simplification is found on all sides of the political divide.

The internet is a machine that devours trust and our ability to do democracy, is Green's exasperated conclusion.

We do not know if misinformation is worse now than at most other times in history. But it is different. It is probable that more people than ever are engaging in political discussions about national and global matters because more people have access to information on such matters, and social media platforms encourage engagement.

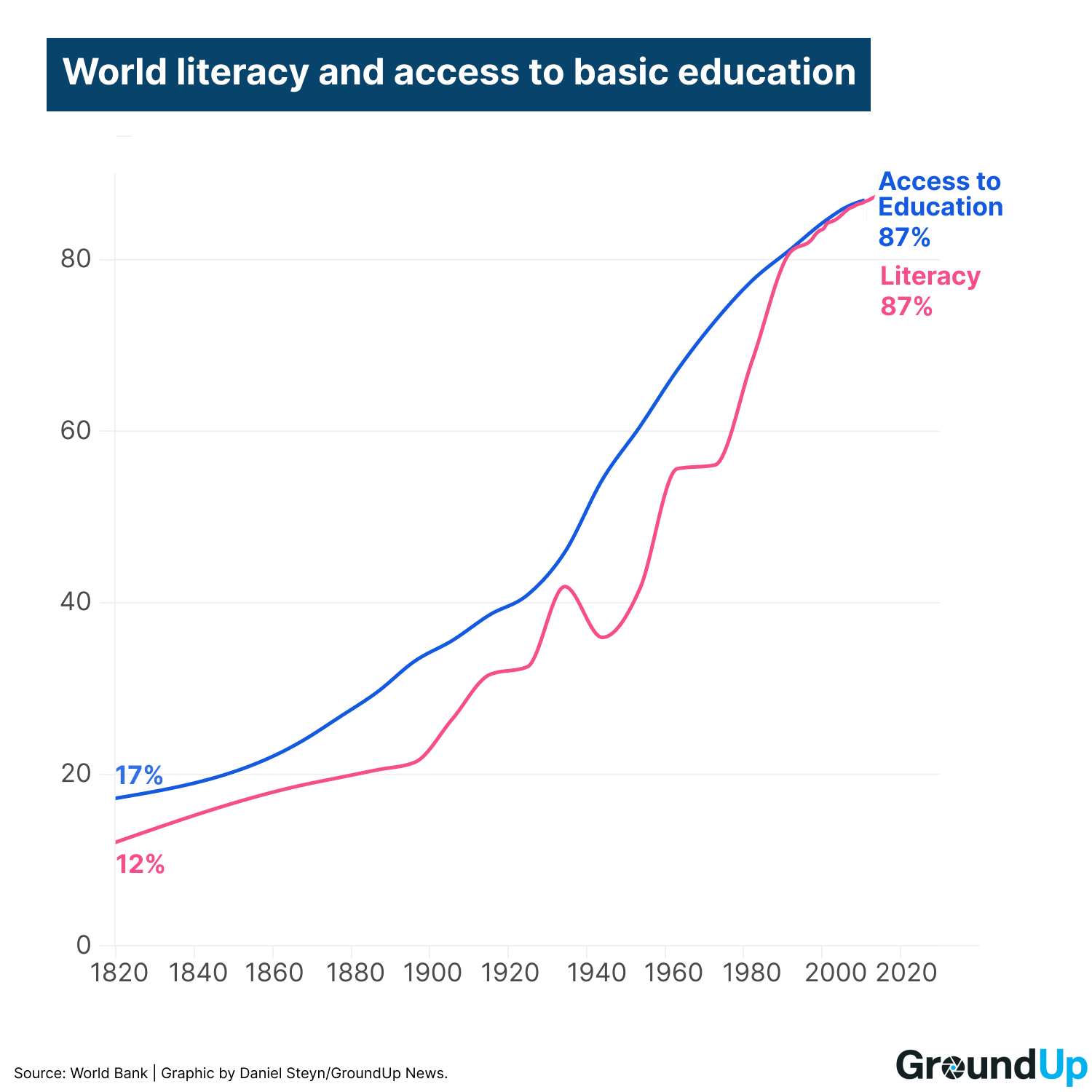

The world is more literate than ever before, and distance has largely been removed as an obstacle to the communication of ideas. This has enabled greater political participation.

More politically active citizens should be a good thing. But misinformed and misled active citizens are potentially a menace. We saw this before the proliferation of digital platforms. Stalinist Russia, Nazi Germany, the Cultural Revolution in China, the US war on Vietnam, the Rwandan genocide — the 20th century has sufficient examples of large numbers of people being so badly misinformed that they become complicit in mass murder.

We are seeing now, for example in the Russian war on Ukraine, the Israeli occupation of Gaza and the West Bank and the civil war in Sudan, how engagement-driven digital platforms replete with misinformation and bias can be used to encourage or justify mass murder and ethnic cleansing. On the other hand, we are also able to be more aware of atrocities happening far away from us, and this offers opportunities for people across the world to organise to try to stop, or at least mitigate, these atrocities.

We are also in a time of unique existential challenges: climate change, civilisation-destroying weapons, and new high-tech tools, particularly artificial intelligence, with which to generate misinformation. Mass participation in public discussion to address these challenges should be welcomed, if that participation is well-informed.

It is in the interests of the vast majority of us, across the world, to be informed. But we are all at ongoing risk of being systematically misinformed. Being misinformed weakens our ability to participate constructively in public discussion, in elections and in public life generally. In the face of existential threats, engaged, well-informed citizens across the globe are vital.