3. Platforms versus publishers

In May 1945, soldiers who collaborated with the Nazis were directed by British authorities to surrender to Yugoslav partisans near the Austrian town of Bleiburg not far from the Yugoslavian border. Thousands of these men were subsequently executed by the Yugoslav authorities. In 1986, Nikolai Tolstoy — a British monarchist and descendent of the famous author whose surname he shares — wrote a book, The Minister and the Massacres, in which he held former British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan and Toby Low, aka Lord Aldington, responsible. He also published a pamphlet which made similar accusations.

Aldington sued Tolstoy. In 1989, a jury awarded him 1.5-million pounds. It was the biggest libel damages award in UK history. Aldington also sued the publishers of The Minister and the Massacres, who settled the case, agreeing to pay the lord 30,000 pounds and not republish the book.

The amount awarded against Tolstoy is generally agreed to have been unfair. Defamation and libel suits hardly ever result in awards anything close to that, at least outside the United States.

An interesting hypothetical question arises: if Tolstoy had published in 2025 on Facebook, could Aldington have sued Facebook as opposed to Tolstoy’s 1980s publisher? Such a suit would have no chance of success in the United States. And even in the UK it seems unlikely to succeed. The reason is that legal jurisdictions appear to view Facebook as a platform, not a publisher, and the legal standing of platforms is different. This is explicit in US law.

Jeff Kosseff’s book The Twenty-Six Words That Created the Internet explains the US law that makes it possible for digital social media platforms to exist without being sued into oblivion. The 26 words are from Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act:

“No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.”

Because of this law, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, BlueSky, WhatsApp, TikTok, and YouTube cannot be successfully sued for libel or copyright infringement for third-party content appearing on their platforms. There may be the caveat that content has to undergo some kind of automated moderation and law-offending content removed, perhaps only when it is brought to the notice of the platform. But whichever way it is interpreted, the legal responsibilities of the platforms for the content published on them are far less onerous than for publishers of books, newspapers and online news sites.

This is not a bad thing. Social media sites would not be possible in a legal environment where they could be automatically sued for content posted by their users. In contrast to, say, a book publisher, there is almost no pre-publication vetting of content by platforms. Nor is such vetting technically feasible, and it is doubtful it is desirable.

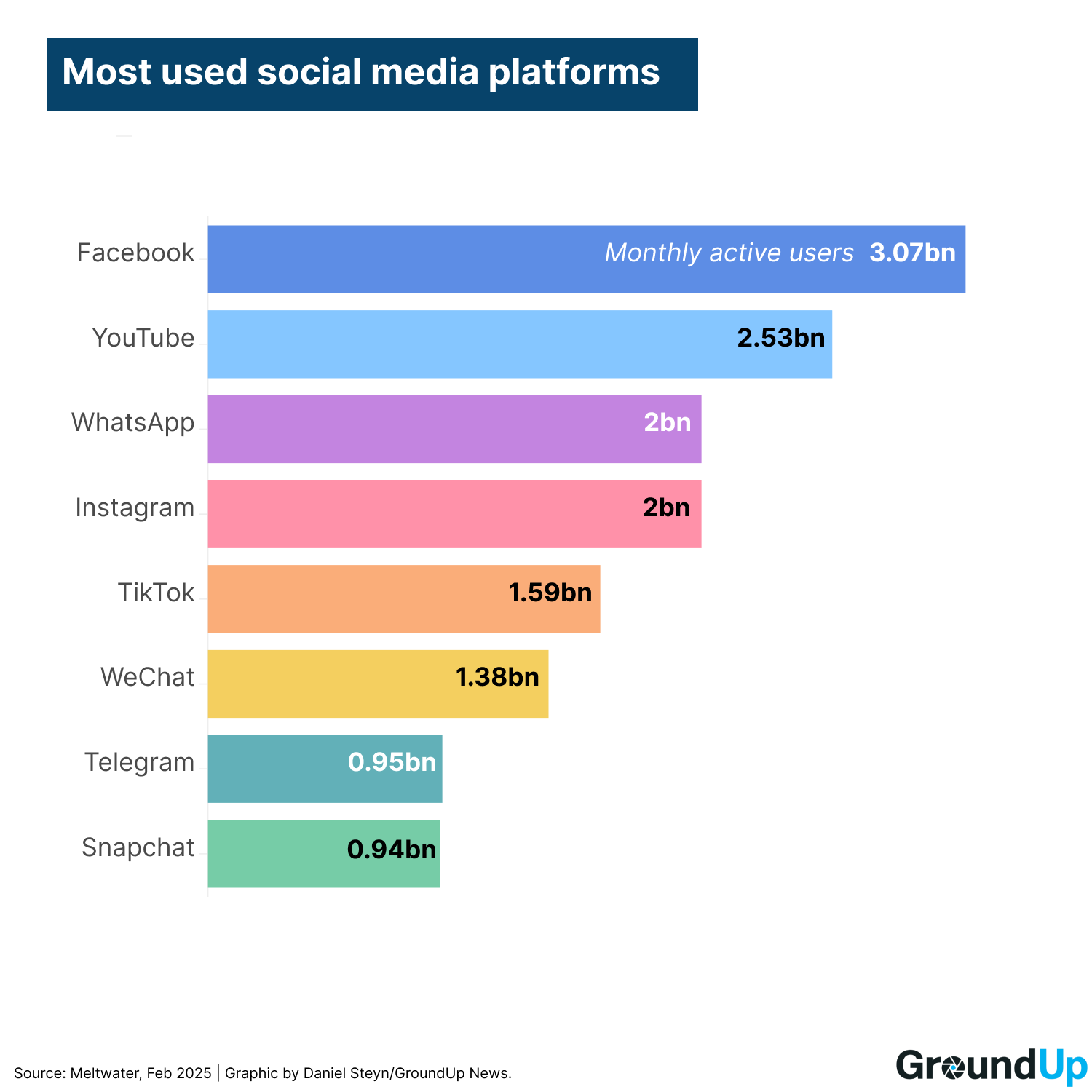

But being considered a digital platform — not responsible at the point of publication for what users post — as opposed to a publisher like the New York Times, is a legally privileged position. The internet is dominated by a handful of these platforms. The major platforms are owned by large companies controlling the flow of news to most people in democratic countries. Daily, billions of people engage with the multitude of news articles, commentaries and alleged facts that flood these platforms. All have algorithms to filter what their users will likely read. These algorithms are by and large not optimised to filter this huge volume of content for accuracy and relevance. Instead they are optimised to keep users continuously engaged on the platforms.

Consider one platform not mentioned above: Google Discover. It isn't strictly speaking a social media platform because users don't communicate with one another using it. Nevertheless, it is installed on Android phones and it delivers a stream of news articles. This is an enormous market share. About 70% of cell phone users, or over 3-billion people, use Android phones. To its credit, Discover does deliver a lot of quality articles — if it was entirely useless it would not be used — but it also delivers a fair chunk of junk, articles seemingly selected because of hyperbolic clickbait headlines. Many of these articles appear to be regurgitated AI-produced nonsense, especially in science and technical fields.

Discover exemplifies a platform that is not optimised to inform, but to keep you clicking on links, seeing adverts and preferably clicking on those too. It’s a brilliant business model for Google, dodgy publishers and advertisers. Google’s systems offer a perverse incentive to create low-quality, frequently inaccurate garbage.

Consider these facts:

- Platforms depend upon a legal privilege for their business models to succeed, i.e. Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act.

- These massive platforms increasingly dominate the information that billions of people receive.

- The platforms are, for the most part, not optimising the filtered information they provide to their users for accuracy and relevance.

For years people have been complaining about this. Brilliant documentaries have been made. Numerous books have been written. The lamentations about living in a post-truth world have become a cliche. We do not believe that this should simply be allowed to continue. We are proposing that something be done: the recognition of a right to be informed that becomes enshrined in law, a tool to hold the platforms accountable.